Professor Rae Frances has written and co-authored many books relating to women at war both at the battlefront as nurses or back at the homefront organizing things to be sent to the soldiers.

She looked at some artefacts lent to the university for the 100 stories project. These were:

- letters written by a matron and sent home to a dead soldier’s mother

- medal sent by government to mother of soldier who was killed

- instructions for knitting socks

Many historians used the term ’emotional labour’ to describe the work done by women to help their sons, husbands, fathers who were at the battlefront.

Many Australian nurses were disillusioned with the “Mother country” (Britain) where they saw stuffy and pompous people and a society where there were different classes. Yes Sir, No Sir from the British while the Aussies were more larrikins. They also wanted the wide open spaces of Australia instead of the cramped, manicured areas of Britain. They were now longing for Australia as their nation rather than Britain. They could see the positive sides of living in Australia rather than in the “old country” of England.

Nursing also became more of a profession from WW1 where opportunities to do surgeries and provide anaesthetics were given to nurses. But upon returning from war, nurses also suffered from what we now term PTSD – post traumatic stress disorder. Some nurses who survived the war also returned to civilian life and began Nursing Unions as they now had more skills learnt on the battlefield.

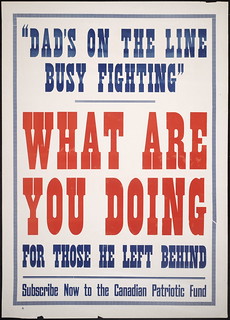

Back on the homefront, it was often the middle class women who organized ways for women to help their soldiers who were fighting. Women in many factories around the country ran programs to make comfort packages, raised funds both in and out of their factories but would often come back during the evening to work voluntarily to make more clothing for the troops.

This was also a time for women to show their initiative, travel broadly and begin careers that would last them through their lifetime. Some women who were opposed to women’s rights (they thought they should be staying at home looking after the husband and family) now started speaking out about conscription and changing their view of the women’s roles in the modern world.

Sex was something not spoken about by governments or army officials which is probably why Ettie Rout was disliked by many. Yet her prophylactic kits and safe brothels certainly allowed soldiers to feel more comfortable about having sex during wartime. It also helped families when soldiers returned home and they didn’t have any sexually transmitted diseases. Australian men, being the furthest from home, were more likely to get VD than the British, where men on leave could go home to their families.

Readers: Were we a class-less society here in Australia before World War 1?