Mum and Sibyle have been friends for ages through the Girl Guide movement where they were both commissioners at some stage and members of Trefoil. A few years ago they were travelling back from a meeting in Launceston via Evandale where many of my COLGRAVE and DAVEY relatives were born. Mum pointed out a house where her great aunt Ethel lived and mentioned she had brought me up there one time when I was a baby. To mum’s surprise, Sibyle said Ethel was her cousin – in fact they were first cousins once removed.

So how are mum and Sibyle related?

They both share Francis COLGRAVE and Isabella WATKINS(ON) – Sibyle through her grandfather Samuel Colgrave and mum through her great grandfather Francis John Colgrave, sibling to Samuel.

Sibyle turned 100 last year and as she is one generation older than my mum, I thought I would ask if I could get her DNA tested. She said yes, so I spent a fantastic afternoon in the nursing home, chatting to Sibyle while she worked up enough spit to put in the tube to send back to Ancestry.

Wait …wait … wait …

Two nights ago, the results came in. Now as 2C1R I was expecting to see mum and Sibyle sharing at least some DNA but when I went to shared matches for mum, Sibyle was not there. Why not? I asked on a Facebook DNA group was it unusual for 2C1R not to share DNA and had many replies but one was from Blaine Bettinger who had written a great post about just this problem.

Yesterday I uploaded Sibyle’s DNA to Genesis. This is the next version from Gedmatch. It allows people to compare others who have tested with other DNA companies not just Ancestry. Because of the algorithm used by Ancestry some smaller segments might not be included in their results, so I was hoping those smaller segments would be there in Genesis.

More waiting … but using the one to one comparison, I found mum and Sibyle did share DNA but only 18cM over two segments which should mean they relate about 5 generations back.

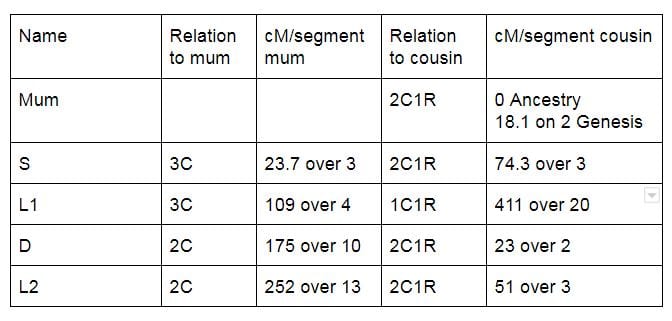

I then decided to compare the amount of DNA from matches shared by both mum and Sibyle. The results in the table are from Ancestry other than the one where I have Genesis.

Readers: Has anyone else had a surprise when there was no DNA when you thought there should be especially with closer relatives?