Most of the information in this post was found when I visited Ireland to do research on the Jackson family. It comes from visits to the National Archives of Ireland in Dublin, the Lifford Courthouse and Donegal archives in Lifford, County Donegal and a quick visit to the Mellon Centre for Migration Studies at the Ulster American Folk Park in County Tyrone.

My great great grandmother Rebecca Jackson was sentenced to seven years transportation on 1 January 1847 at the petty sessions court at Lifford in County Donegal. She was sentenced with three other members of her family: her father William, her younger brother William and Jane Steele (not known yet how she is related). But you ask how is this related to the title of my post?

Anne Jackson, yet another member of the family but still not proven how related, was also a member of the Jackson gang who had been stealing for many years in the Carrigans area of County Donegal. But on 1 January 1847, she turned on the gang and dobbed them in to the authorities.

Three cases were reported on that day:

- Anne Jackson of Garsney??? and John Craig of Corneamble a(gainst) William Jackson the Elder and Jane Steel both of Garsney

- Anne Jackson of Garsney and Anthony Gallagher of Ruskey? a(gainst) William Jackson the Elder, William Jackson the Younger, Rebecca Jackson, Jane Steele and Mary Jane Gallagher

- Anne Jackson, Caldwell Motherwell of Monglass, sub constable James Love?, Nelly Jackson of St Johnston and Joseph Wray of Curry free? County Derry a(gainst) William Jackson the Elder, William Jackson the Younger, Rebecca Jackson, Jane Steele and Mary Jane Gallagher

Remember this is the time of the potato famine in Ireland, so was William and his family stealing just so they could eat and survive? What would happen to the rest of the family once they were convicted and sent to prison or transported to Van Diemens Land?

Anne Jackson very quickly found out that the remaining members of the Jackson family could turn against her. The following information found in the Donegal Outrage Papers at the National Archives of Ireland.

By May 1847, Mr McClintock and John Ferguson (from the Newtown Cunningham Petty Sessions) had sent a letter to the Under Secretary at Dublin Castle applying on her behalf for a passage for Anne and her two children to one of the colonies at Government expense. The reason for this request was she had been threatened with personal injury from other family members still in the county. Anne was a pauper, unprotected and had two children aged 10 and 6 to look after.

A month later, a reply came from the the Government Emigration Office in Londonderry.

I beg to acknowledge the receipt of your letter of 22 Instance respecting the providing passage for Ann Jackson and her two children and to arrange for 5 pound to be paid her on arrival at the port of Quebec. Have received from H McMahon Esq fifteen pounds for the purpose of providing such passage and remitting the five pounds – I shall provide the passage and remit the pounds to the Emigration gent at Quebec.

Quarantine station on Grosse Ile, Quebec, Canada

By 4 May, Dr Douglas and his staff were ready for the ships arriving from Ireland. There was one steward, one orderly and one nurse as well as the doctor. They had 50 iron beds and lots of straw, ready to hold 200 cases for quarantine. The rest of the island was very marshy so not really suitable for extra tents to be erected to expand the quarantine station.

But by December 1847, Dr Douglas reports the following statistics:

- inspected 442 vessels – mid May to mid December equals 7 months, therefore roughly 63 vessels per month or 2 vessels per day

- 8691 emigrants taken into the hospital, sheds and tents with typhus and or dysentery

- 95 smallpox cases and 25 other diseases

- 3238 dead: 1361 men, 969 women and 908 children

To read more about the conditions of ships and emigrants, check out this information from Padraic O’Laighin. More reading about the coffin ships and journey to Canada is found here.

In my research, I found a list of passengers booking for the ship Superior (570 tons Captain Mason) for Quebec 5th-16th July 1847. On board was Ann Jackson, Carrigans, Co. Donegal and children Mary Jane 13 years and Robert 9. Had Ann misreported the ages of her children as 10 and 6 in order to get more sympathy from Mr McClintock? Or is this not my Ann?

Looking at immigrants with surname of Jackson at Grosse Ile Quarantine Station 1832 – 1937, there is mention of chattels belonging to Ann Jackson, a deceased person. Her name is also included on the station memorial. There is no mention though of Mary Jane or Robert on these records. Did the children survive the journey and then adopted once they landed in Canada? I have not researched further on these two but do have some DNA matches on mum’s side in Canada whose trees go back to a Jackson surname.

As part of the UTAS diploma of family history, I wrote a couple of stories relating to Anne – one about Garshooey townland (is this the Garnsey mentioned in the cases above) and a fictional piece about Anne’s last day on Grosse Ile.

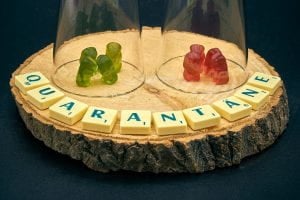

Readers: How are you coping with lockdown, quarantine or isolation during this time of Covid?