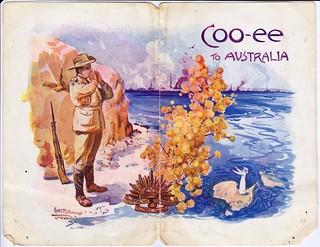

This, the third week of the course, looks at the other ANZAC – how multicultural was the A.I.F. during WW1?

The stories this week included:

- Peter Rados – Greek born Australian immigrant with parents and sisters living in Turkey

- Peter Chirvin – Russian born immigrant who died on the ship home after ridicule from shipmates

- Cornelius Danswan -first generation Chinaman with an English mother

- Abas Ghansar – born in India, came to Australia but could be deported at any time

These four stories showed how the “non white” soldier was treated especially by bureaucracy after the war was over. Having lost so many soldiers in the early battles, the recruitment officers would take anyone during the last couple of years of the war. They were then used as cannon fodder in the battles in Europe. Australia at this time had a form of white Australia policy and made it hard for non white people to live decently in the country.

But as many commenters mentioned, the aspect of pensions also affected the white soldiers. Who got pensions? Why were some cut? Were white and non white soldiers treated differently with pensions?

The next stories looked at the indigenous soldiers here in Australia

- Alexander McKinnon – mother received parcel but gratuity went to protector of aborigines, medals to stepmother

- William Maynard – one of three brothers sent to war and body is still missing

- Rigney brothers – sand of birth country intermingled with sand of death country

- James Arden – stood up for his rights and entitlements

My reflection:

All four stories were compelling but for different reasons. I felt for “Cobb” in not receiving her son’s medals but I felt most proud of James Arden for standing up to white authority of that time and in using his entitlements to help his whole community not just his family.

I wonder how the New Zealand government are going to treat my ANZAC soldier who had a father who was Afghan and a mother who was Australian? Find out more on my blog when I have done the research. https://suewyatt.edublogs.org